‘Imagine an eye unruled by man-made laws of perspective, an eye unprejudiced by compositional logic, an eye which does not respond to the name of everything but which must know each object encountered in life through an adventure of perception. How many colors are there in a field of grass to the crawling baby unaware of ‘Green’? How many rainbows can light create for the untutored eye? How aware of variations in heat waves can that eye be? Imagine a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement and innumerable gradations of color. Imagine a world before the ‘beginning was the word’.

– Stan Brakhage, Metaphors on Vision

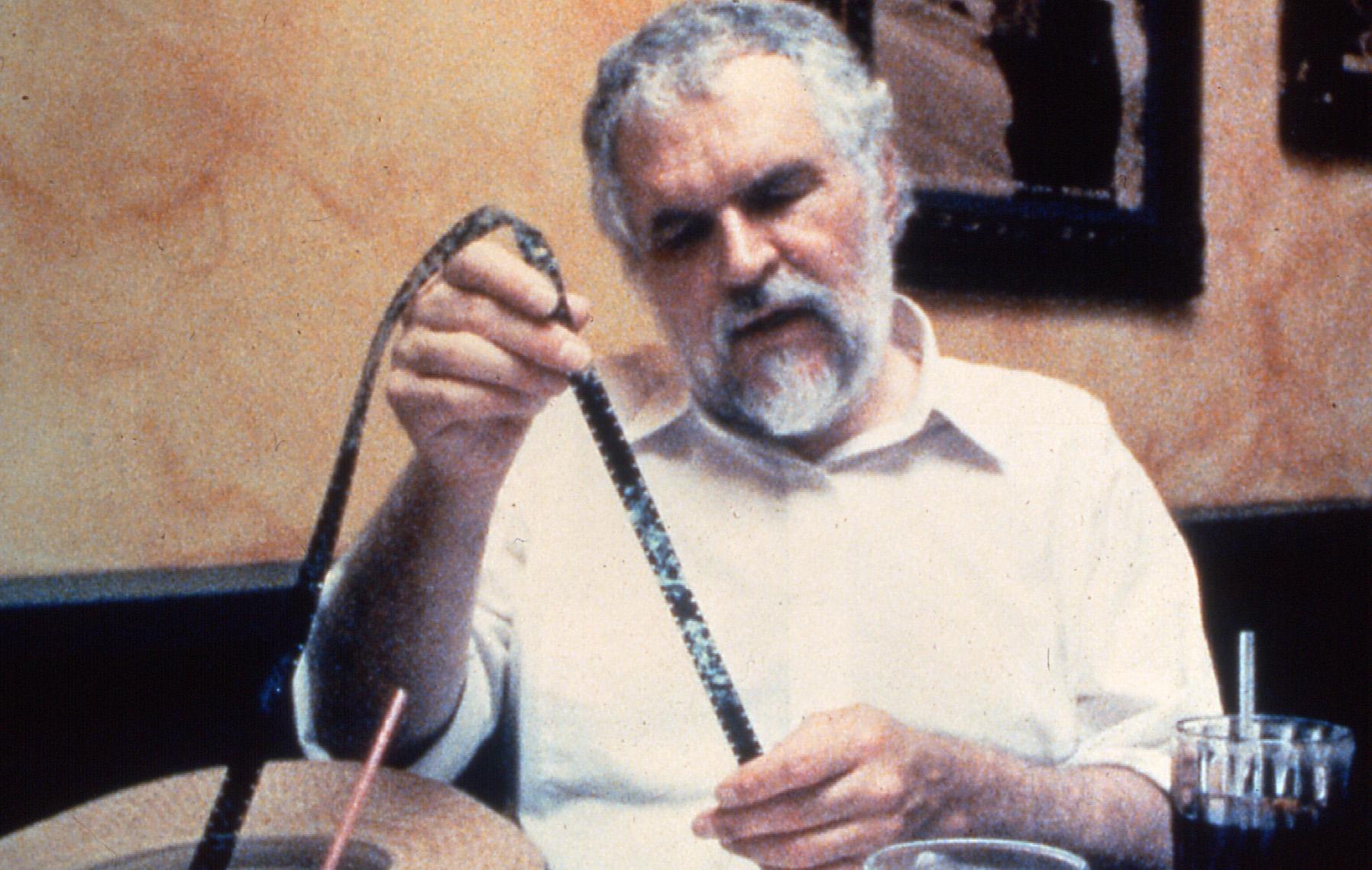

Stan Brakhage is widely regarded as being one of the most important filmmakers America has ever produced. Along with Maya Deren and Kenneth Anger, he is the most widely known of the post-war American experimental filmmakers. His work has had a profound impact not only upon the underground film community of which he was part, but also within the widespread domain of mainstream filmmaking itself. His particular aesthetic can be found in the opening credits of David Fincher’s Seven, and in the end sequence of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ. In the realm of popular culture, his students at Bolder Colorado University included Trey Parker and Matt Stone of South Park fame, and their character in the series, ‘Stan’, is named after the filmmaker. Most significantly however, Brakhage’s impact upon the underground film community of the Western world was immense. As Jonas Mekas, the cinephille and filmmaker noted, “after Brakhage, nothing was the same again”.

Brakhage’s entire oeuvre can perhaps be summarised in a single statement by a personal friend and lifelong champion of the artist, Fred Camper: “Brakhage wants to make you see”. ‘To see’ Brakhage affirmed, was not just to perceive the visual field as we have been conditioned to perceive, in a form that is implicitly defined by the acquisition of language and the overarching effect of habitual repetition, but rather to perceive things ‘as they truly are’. The overarching aim of his work was to render the visual field in it’s pre-linguistic state and a prompt a possible ‘remembrance’ of the state of innocent, naked vision; one that is aware and open to the ‘eccentricities’ of the visual processes that have been disregarded by sociologically formed models of what is deemed to constitute ‘seeing’, with examples of such phenomena including closed eye vision, hypanagoic vision, and the emergence of phosphenes in the retinal field. Brakhage believed that such forms are vital and undervalued attributes of the visually perceptive process, that the entirety of the visual field must be accurately represented and taken into consideration, both within an aesthetic context and within the subjective visual experiences of the individual. When Brakhage was a child, he suffered from very poor eyesight and wore very strong corrective glasses. He decided to throw the glasses away, deciding that his natural manner of visual perception was just as valid as those with ‘correct’ vision. Brakhage described himself as “the most thorough documentary maker in the world, as I document the very act of seeing itself”. He refused to differentiate between the visual act and the activity of memory and imagination, as he believed vision to be the primary perceptual mode in which other respective physiological experiences intertwine. Vision, for Brakhage, constituted the referential and perhaps homogonous form of the perceptual apparatus.

Brakhage’s desire to render a form of ‘innocent vision’ was influenced by his deep interest in Romantic and Modernist poets and philosophers, including Schopenhauer and Rimbaud. In relation to static aesthetic forms, Brakhage frequently drew comparisons with his practice and that of the aesthetic concerns of the abstract expressionists of the mid part of the 20th century, namely Pollock and Rothko. Comparisons may be drawn in the manipulation of the ‘canvas’ – in this case the film stock – in which the work is imbued with the artist’s psyche in the act creation. Influenced by poetry as much as the visual arts – particular the work of Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein and Charles Olson – Brakhage was a pioneer in the method of physically manipulating celluloid. He painted on, scratched, burnt, and even urinated on the film in order to physically alter the source material of the ‘light visions’ he created. Unwilling to work with images accompanied to music, though his exquisitely rendered editing he made the images themselves project a rhythm of their own, much as poetic verse in the written word does. His prodigious output resulted in him being an immensely prolific filmmaker, producing more than 300 films over the course of his working life.